A Colonial Christmas

As part of our tree lighting and holiday event on Dec. 3, we interpreted three of our historic buildings to represent Christmas during that period. The Old House, a colonial Christmas; the Wickham House, a Victorian Christmas; and the Schoolhouse, a mid-century Christmas. We will be releasing three consecutive blogs that will talk about each of those periods, starting with this one, a colonial Christmas.

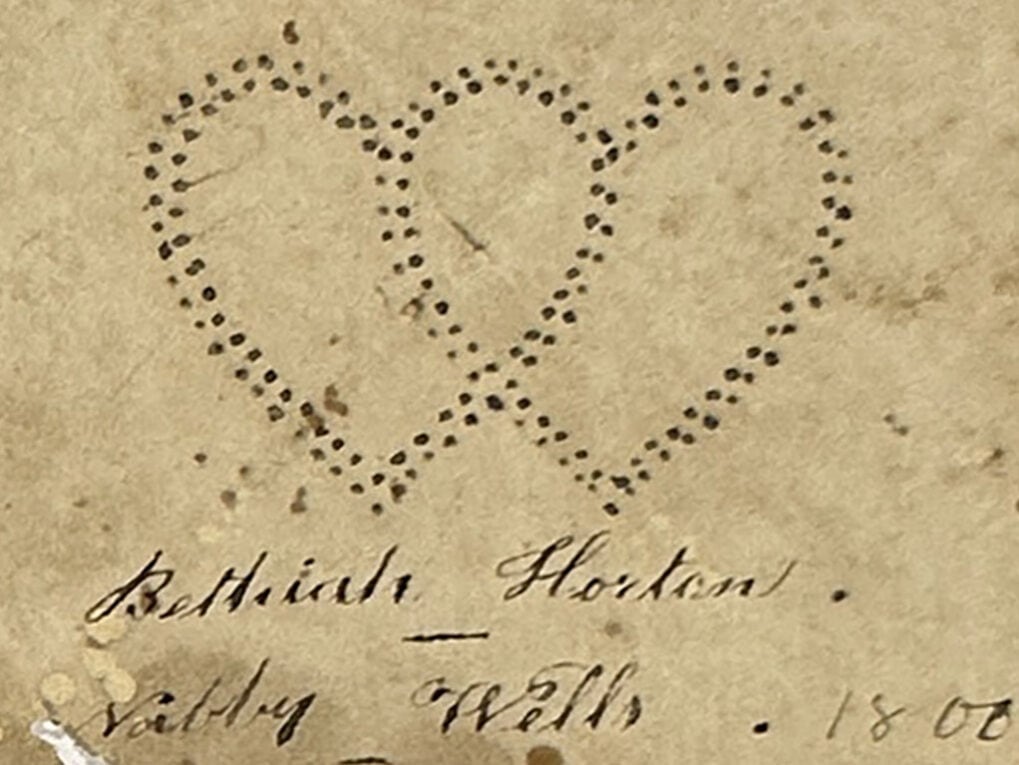

Christmas during the colonial period in America was very different from what is celebrated today. The early New England colonists, the Puritans, denounced Christmas altogether, claiming it was too pagan. They treated it as a typical working day and even went as far as creating laws against the celebration of Christmas. The 40 families that left New England did so to escape the overly strict religious dogma of the Puritans, so it could be assumed they had a more relaxed view of the holiday and brought with them some of the traditions they enjoyed in England. This included having December 25th as the first day of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Over those twelve days, there would be feasts, special services at the church, visiting family and friends, and one or more parties, depending on your social standing. Usually, the last day of Christmas was seen as the prime merrymaking date.

Nevertheless, the harsh realities of early colonial life, in particular during the winter, more than likely significantly impaired or reduced the celebrations. The focus of the holiday at the time was Jesus and parties. People did exchange gifts, but it was not considered crucial. Most of what we would recognize as key points of Christmas were not around or practiced at the time. They were probably not exposed to German customs, such as Christmas trees (and if they were, they would have thought these customs odd), and Dutch traditions, such as St. Nicholas and stockings, may have been known. Still, relations with the Dutch were not good, and they probably would not have thought to adopt any of their customs. They still would have thought that elaborate or excessive celebration was “Papist,” a part of the Catholic religion they rebelled against.

Although many people think of pomander balls (oranges with cloves stuck in them) as colonial, they were actually Victorian. The root of this cultural confusion can be traced to Colonial Williamsburg. Back in the 1930s, a large sum of money was donated to Colonial Williamsburg to create Christmas decorations for the holiday season. The museum did not want to do something modern, worrying it would ruin the historic atmosphere. They could not do something colonial because the colonists did not decorate for Christmas. So as a compromise, they decorated in a Victorian style, historical but not colonial. The association stuck, and to this day, while Colonial Williamsburg will be the first to tell you pomander balls are Victorian, the general public still sees them as colonial. Although the traditional “colonial Christmas front door,” festooned with greens running up the side, a wreath in the center, and fruit crowning the top, was probably more of a southern tradition, we took some geographical liberties and decorated the Old House door in that style. In fact, the southern colonists more actively tried to duplicate traditional English Christmases, including some Anglican traditions such as celebrations including feasting, gambling, drinking, wassailing, masquerade balls, and decorating with greenery, berries, and fruit. By the 1620s and ‘30s, Christmas was established as a benchmark in the legislative calendar of the Virginia colony. For example, laws on the books in 1631 stated that churches were to be built in areas that needed them before the “feast of the nativity of our Saviour Christ.”

How ever Southold colonists celebrated Christmas; it was probably more than the Puritans and significantly less than the elaborate way it was soon to be celebrated in Victorian times.