I was invited by the president of the Southold Indian Museum, Dr. Lucinda Hemmick to attend their Artifact Day on May 1, 2022. It was decided that we had too many artifacts to even think about bringing to the event, so we made an appointment with Indian Artifact expert Efraim Horowitz to come view our collection.

The impetus for the artifact day was to start a project using ArcGIS (Aeronautical Reconnaissance Coverage Geographic Information System). ArcGIS Online is a cloud-based mapping and analysis solution. It is used to make maps, analyze data, share information, and collaborate. It has many varied uses but of concern to Mr. Horowitz is that it can link information and objects to locations, which is ideal for the study of Indian artifacts since knowing where they were found is an important part of understanding their history and linking them to their story. It is often the only piece of provenance that is connected to these artifacts.

Because our collection is extensive, he included Shane Weeks, Cultural Consultant for the Shinnecock Nation and Co-Chair and Co-CEO of the Niamuck Land Trust. Mr. Weeks and Harry Wallace, Unkechaug Nation Chief and Dartmouth trained lawyer.

Needless to say, the group was thrilled and impressed with our collection, noting that many of the objects were 10,000 years old and there were spearheads known to be used to hunt Mastodons. They were allowed to examine some of the artifacts that were not on display. Some of the collection was from New England tribes. These artifacts are commonly found on Long Island because they were brought down during the ice age.

He noted that the Fleet arrowhead collection, some of which is arranged in the shape of a large encased arrowhead, had historical folk art value in and of itself.

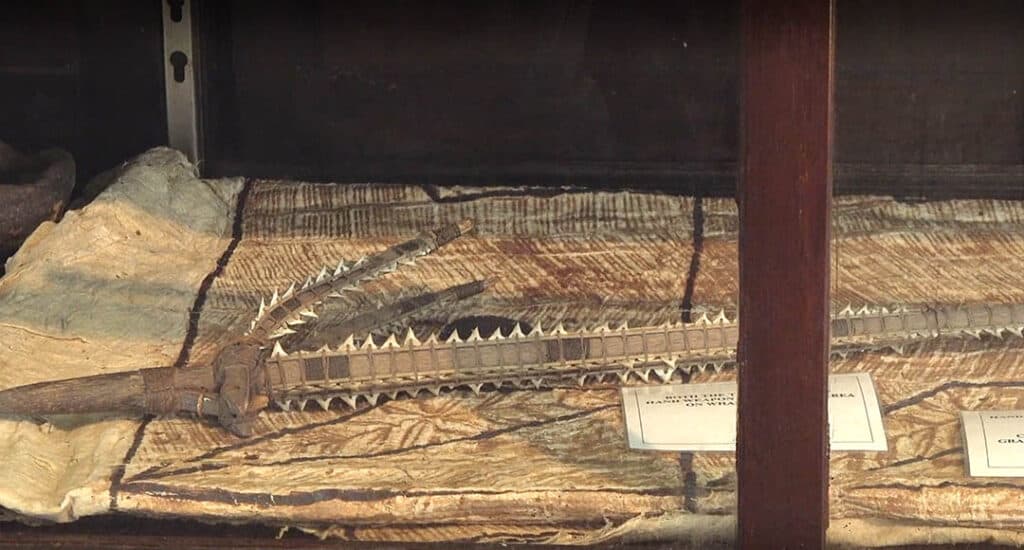

As the group examined the collection in the schoolhouse, the ceremonial sword crafted from Shark’s teeth from the Gilbert Islands with a somewhat cryptic sign stating that it was brought back on a whaling vessel and given to Walter Luce of Cutchogue by a Shinnecock Indian, caught Mr. Week’s eye. He became very excited. It seems he is the decedent of an Indian whaler that sailed out of Sag Harbor and was known to hunt whales in the Gilbert Islands area of the Pacific. He realized that it was extremely likely that his ancestor was possibly the Indian whaler that gave Luce the sword. He became emotional as he said that he had handled so many Indian artifacts, but this was the first time he had ever touched something that was so likely to be directly connected to one of his own ancestors. It was at that moment Mr. Horowitz, a filmmaker and founder of the 1523 Project, a 501 (c)3 non-profit scientific association, decided that he was going to make a short video about the experience. A part of the mission of the 1523 project is to film short, easy-to-digest historical teaching videos. With the approval of the board and my supervision, I gave them permission to film the following video.

More information on Shark tooth sword

The information acquired about our sword comes from the Bowers Museum, Santa Anna, California, a museum with extensive Oceanic Collections. A recent acquisition of two swords almost identical to the one we have in our collection (and also attributed to the Gilbert Islands) compels me to repeat their findings on the history of the sword and apply it to ours.

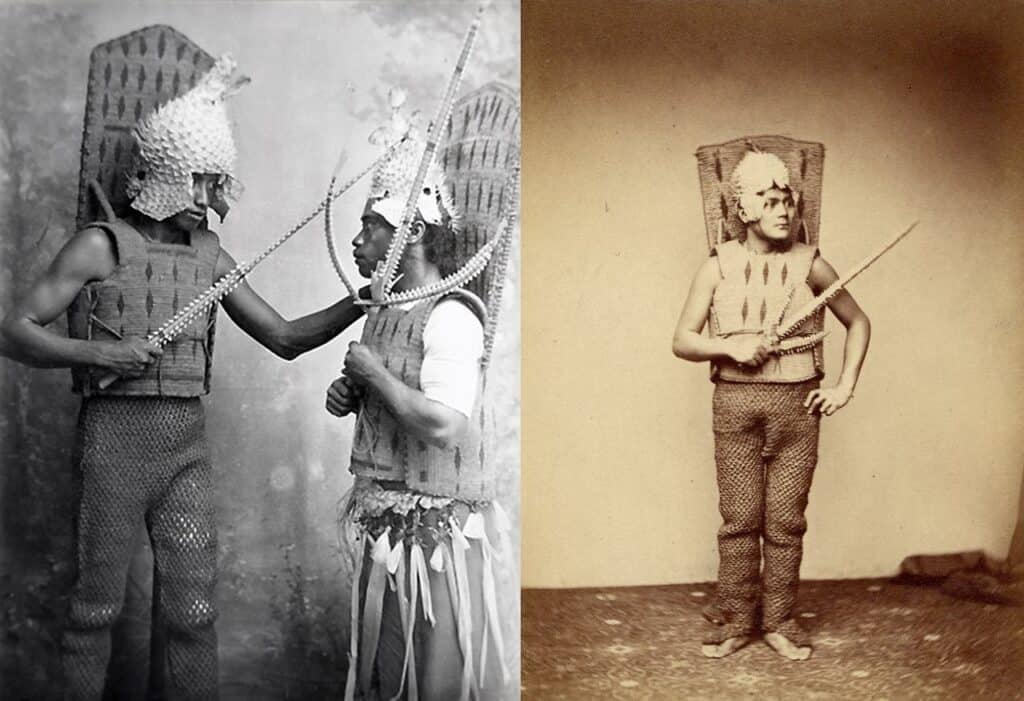

Based on a study of the Gilbert Islands’ weaponry, first published in 1923, thirteen different varieties of weapons were traditionally used on the islands. Ours is a sword club referred to in the I-Kiribati vernacular as te toanea, te winnarei, or te tuangai. The wooden element of the club generally came from coconut wood sanded down to shape, but the major work of the sword went into acquiring and securing the teeth to the blade. Shark fishing was only done by experts. The larger size of the prey required fishermen to travel farther away from shore and employ methods including remarkable deep-sea hooks. When the teeth had been removed from the sharks, two methods were employed to secure them to swords. The first of these was a socketing technique. Small grooves were carved into the wood and the teeth were further stabilized with fiber cord. The technique used in our sword involves drilling small holes through the teeth themselves. Two thicker sections of palm fiber are then used to stabilize the teeth, and a more complex binding is used to ensure that the entire array of teeth is locked in place. This second method allows for the rare underlying layer of bark cloth. The darker sections of fiber wrapping are human hair, used in almost every recorded example of Kiribati weaponry. The purpose of using hair was almost certainly magical—but little is definitively known about it.

Examples in the British Museum and Smithsonian’s collections date the sword back to the 1860s and indicate that these pronged swords were used before Kiribati (the republic of the Gilbert Islands) became a protectorate of England in 1892—the year which effectively marked the end of non-ceremonial I-Kiribati weaponry. The base of Kiribati swords are often rounded, and even if they are not, they tend to narrow towards their lower terminus. While the toothed prongs held the potential to be every bit as dangerous as the primary shaft, their true benefit was the same as the steel partisans or ranseurs of Renaissance-era Europe: they were parrying weapons, highly effective at catching an opponent’s weapon and disarming them. Two methods were used to attach prongs. By far the most common was the use of two to four thick curved branches which were tied to the main shaft with fiber so that the butt of the prong extended a couple inches beyond its intersection with the shaft. The other style, employed in Gilbertese weapons, involved socketing two narrower prongs into the main shaft and again securing them with fiber. This latter method was almost exclusively employed with spear heads, while the former was used with both the pronged short swords and the prongs of long spears. Swords and spears were generally used in unison in the traditional warfare of the Gilbert Islands.