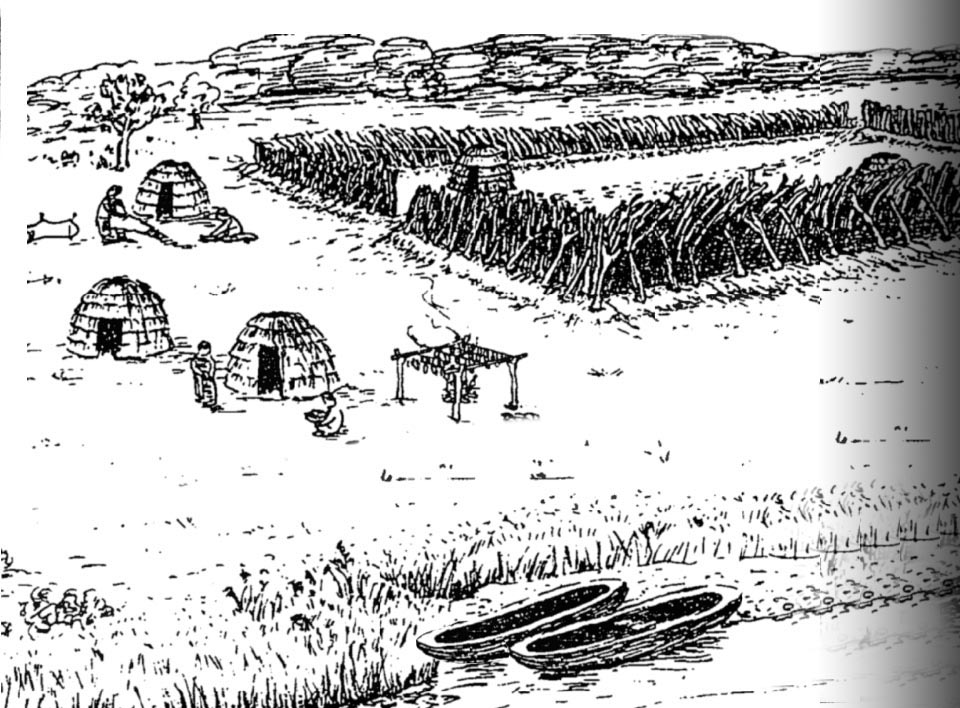

Many of us remember learning that the Indians taught the Pilgrims how to grow corn, by burying fish to fertilize it, and planting seeds over the fish. We were also taught that this was a big part of why those first settlers were able to make it through their early winters. It’s likely when the first 40 families landed on Founders Landing in Southold, not much corn was being grown on the North Fork at that time, but it was readily available through trade with New England. The local Indians kept large stores of this traded corn.

So the North Fork settlers more than likely came with the knowledge of how to grow corn, but the local Indians are said to have shown them a way to process it, creating a more palatable corn product: samp.

In olden times, Samp was often pounded in a primitive and picturesque Indian mortar made of a hollowed block of wood or a stump of a tree, which had been cut off about three feet from the ground. The pestle was a heavy block of wood shaped like the inside of the mortar and fitted with a handle attached to one side. This block was fastened to the top of a young and slender tree, a growing sapling, which was bent over and thus gave a sort of spring that pulled the pestle up after being pounded down on the corn. This was called a sweep and mortar mill. As samp is a dried food, it can be stored indefinitely, providing a staple winter food for early residents. Samp cooked alone is called samp. It is called samp porridge when it is cooked as a main dish with meat and vegetable. Early colonists would keep a stew of samp cooking for several days on the fire since refrigeration wasn’t an option, and the heat would keep any meat in the stew from spoiling. In time, the samp porridge would develop a crust around the pot that would taste like popped corn. This crust would be broken off and given to children as a treat.

The pounding of samp could be heard at a long distance. After these simple stump and sapling mortars were abandoned elsewhere, they continued to be used on Long Island, and an enduring local oral tradition told that sailors in fog could always know on what shore they were and how far they were from the coast when they could hear the pounding of the samp-mortars on Long Island.

In an excerpt from the book, The Algonquian Peoples of Long Island from Earliest Times to 1700 by John A. Strong, described how the native people prepared it:

“The women boiled it until a thick porridge called sappaen was formed. Isaack de Rasieres said that the sappaen was good eating, even better with Dutch butter, and easily digested. Another Dutch observer, Adriaen van der Donck, noted that sappaen was a basic part of the Indian’s daily diet: ‘It is the common food of all; young and old eat it.’ ”

The name comes from the Narragansett word nasaump, which means hominy. Outside of Long Island, it’s called Hominy Grits or cracked corn. Some very old examples and usage of the word Samp comes from the “Dictionary of Americanisms:

Roger Williams describes nasaump as “a kind of meale pottage unparched from this the English call their samp which is Indian corn beaten and boiled and eaten hot or cold with milke or butter which are mercies beyond the natives plaine water and which is a dish exceedingly wholesome for the English bodies” [Key to the Indian Language, p. 33] Samp is still much used wherever Indian corn is raised.

“Blue corn is light of digestion, and the English make a kind of loblolly of it to eat with milk, which they call sampe; they beat it in a mortar and sifte the flower out of it.” [Jouzlyn’s New England Rarities, 1672]

“It is ordered that the treasurer doe forthwith provide tenn barrells of cranburys, two hogsheads of speciall good sampe, and three thousand of codfish to be presented to his Majesty as a present from this court.”[Massachusets Col. Records, 1677, Vol. V. p. 156]

“He slept until the morning light was seen.

Down through the dome to dance upon his brow.

Then Waban woke him to his simple cheer.

Of the pure fount nausamp and savory deer.”

In her essay in the New York Folklore Quarterly, Jeanette Edwards opined that from the time of the first settlers in the 1640’s up to sixty or seventy years ago (approx.1880), samp was cooked all day on Saturday and consumed every Sunday at noon after services in the Meeting House. (Cooking and other work was frowned upon by the East-end church folk, so samp stayed on the fire or was put “down cellar” -the closest equivalate of refrigeration they had until it was warmed up after Sunday service) Many of the descendants of the founding fathers continued making samp in the winter up through the 50s and 60s. A few still do to this day, having shared some of their recipes with “newcomers.”

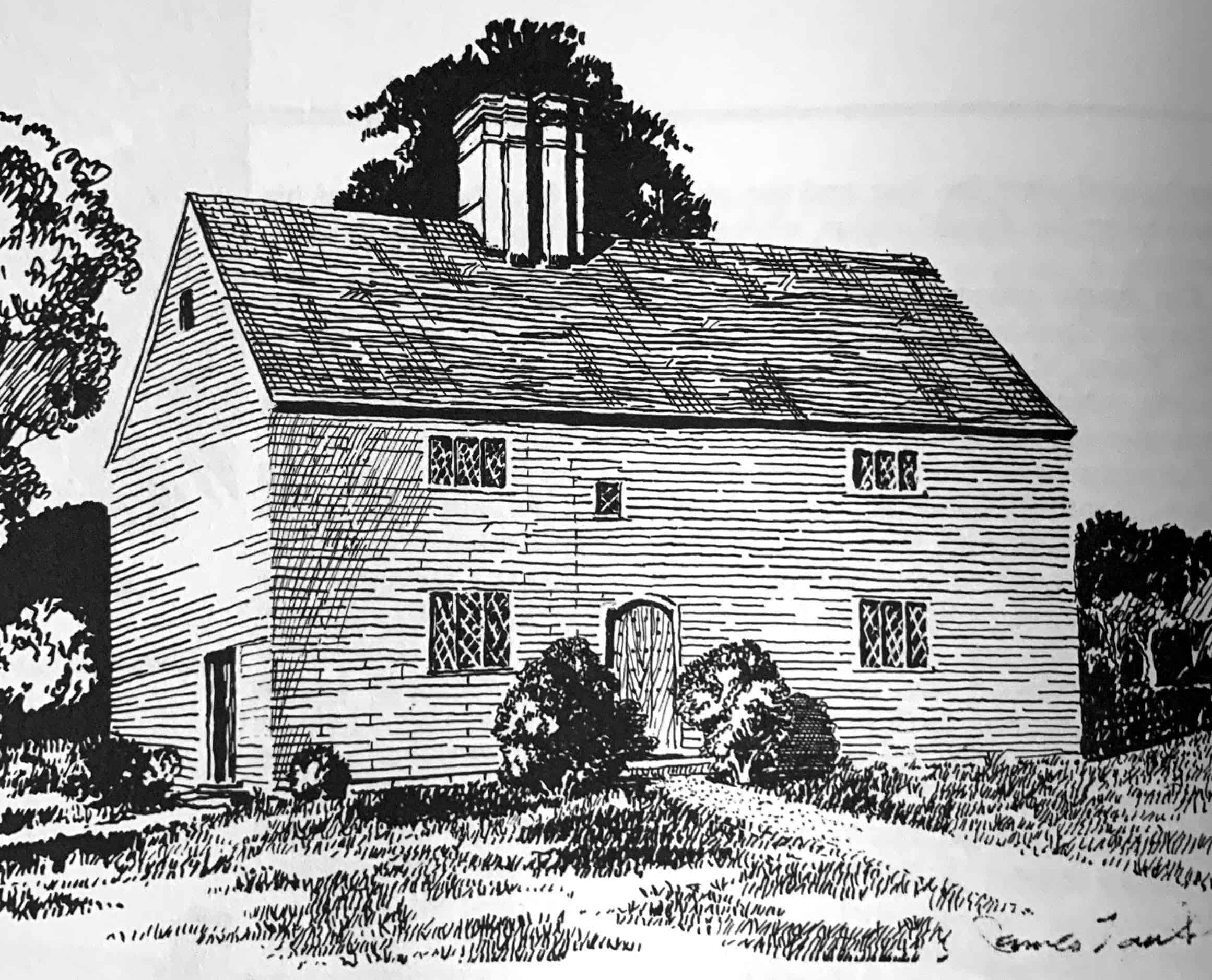

Although the provenance is now unknown, there is a samp mortar and pestle similar to what would have been used in colonial times in the keeping room (kitchen) of the old house.

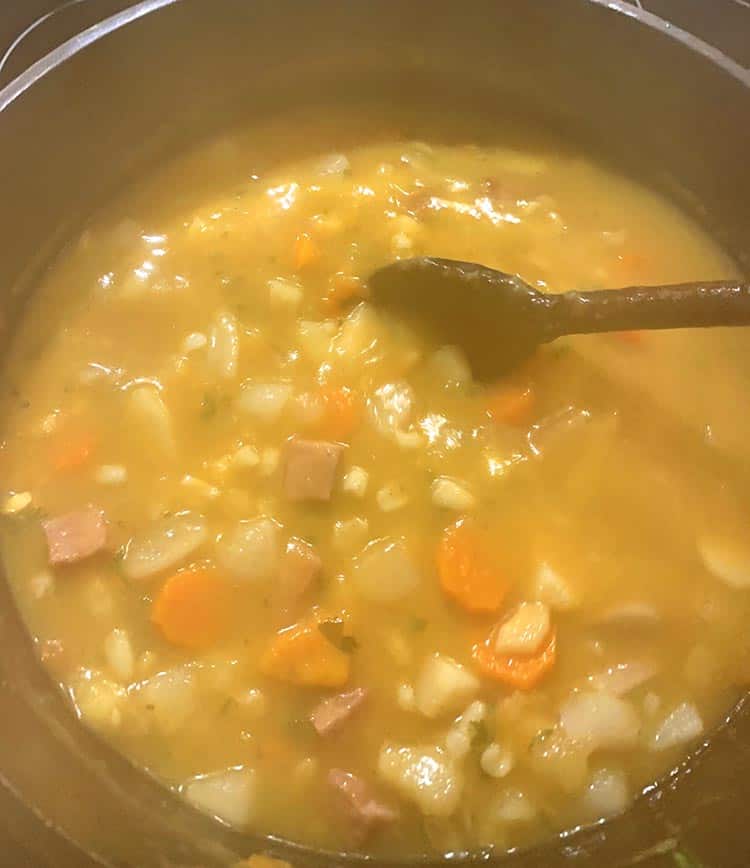

Growing up in Cutchogue during this period, my family often made samp and served it in a stew with beef or ham hocks and root vegetables. In the Cutchogue Methodist Chruch Cookbook, First Edition, Nov. 1958, Winifred Billard writes that there are some families on the Eastern End of Long Island that feel the winter is not complete without a meal or two of samp porridge. She follows with the recipe that my family used to make samp. She claims there is a samp mortar in Willow Hill cemetery, used as a grave marker and bird bath. She repeats a variation of the oral tradition: “Connecticut residents claimed they could hear Long Islanders pounding samp.”

Most of the old recipes used pig knuckles, but when times were hard, a piece of salt pork took the place of other meats, and many families developed their own recipes using chicken, ham, or beef, depending on their tastes and what meat they had available.

Nowadays, samp is hard to come by. For years it was sold in Albertsons store, but they went out of business in the 60s. Today the only place to find it is at the Country Store in Jamesport, and even then, you have to hit him when he’s got it, and if he has it, buy it. He also has a single edition of “Samp, A Traditional Food of Eastern Long Island,” which contains many recipes for making samp. It’s not for sale, but he allows you to take pictures of the recipes in the booklet.

Recipe:

If you know the tradition of samp, it almost seems funny to write a recipe, since cooking samp meant using whatever you had at hand, and in the winter that meant root vegetables.

For the purpose of this article I cooked a samp porridge. My family’s custom was to have ham on New Year’s day, which meant there was always a hambone in the dead of winter to use for samp. I didn’t have a ham bone, so I used what was on hand, a ham steak. On this cold November night, my recipe for Samp Porridge looked like this:

• 1 cup of dried samp (soaked overnight)

• 1 large sweet potato

• 2 medium potatoes

• 1 medium turnip

• 2 Rutabagas

• 1 onion

• 5 medium carrots

• 1 large parsnip

• 2 Knorrs ham bullion cubes

• Ground pepper to taste

• fresh parsley

• 1 teaspoon Bell seasoning

• 2 ham steaks

• 8 cups of water

Dice onions and sautee in the bottom of a soup pan until translucent or caramelized. Cut up all root vegetables. (although I cut mine smaller, most people cut them up the size they would for stew.) Add water, root vegetable and all other ingredients to pan. Simmer for at least an hour. Broth will become thick and glossy, as if you had added cornstarch.

“Samp, A Traditional Food of Eastern Long Island” second printing Sept. 1974. Mary M. Getoff

“Indian Corn,” by Alice Morse Earle. 18th Century History

If You Know This Thanksgiving Dish, You’re an East End Local, By Monique Singh-Roy, November 23, 2016

“Sunday Samp on Long Island,” Jeanette Edwards Rattray, New York Folklore Quarterly; Cooperstown, NY Vol, 9, Issue 1 1953

Stories of pioneer life for young readers. Boston: D.C. Heath & Co. 1900.

“Dictionary of Americanisms, 2nd ed. enlarged” by John Russell Bartlett (Boston: Little Brown.1877). Page 549.